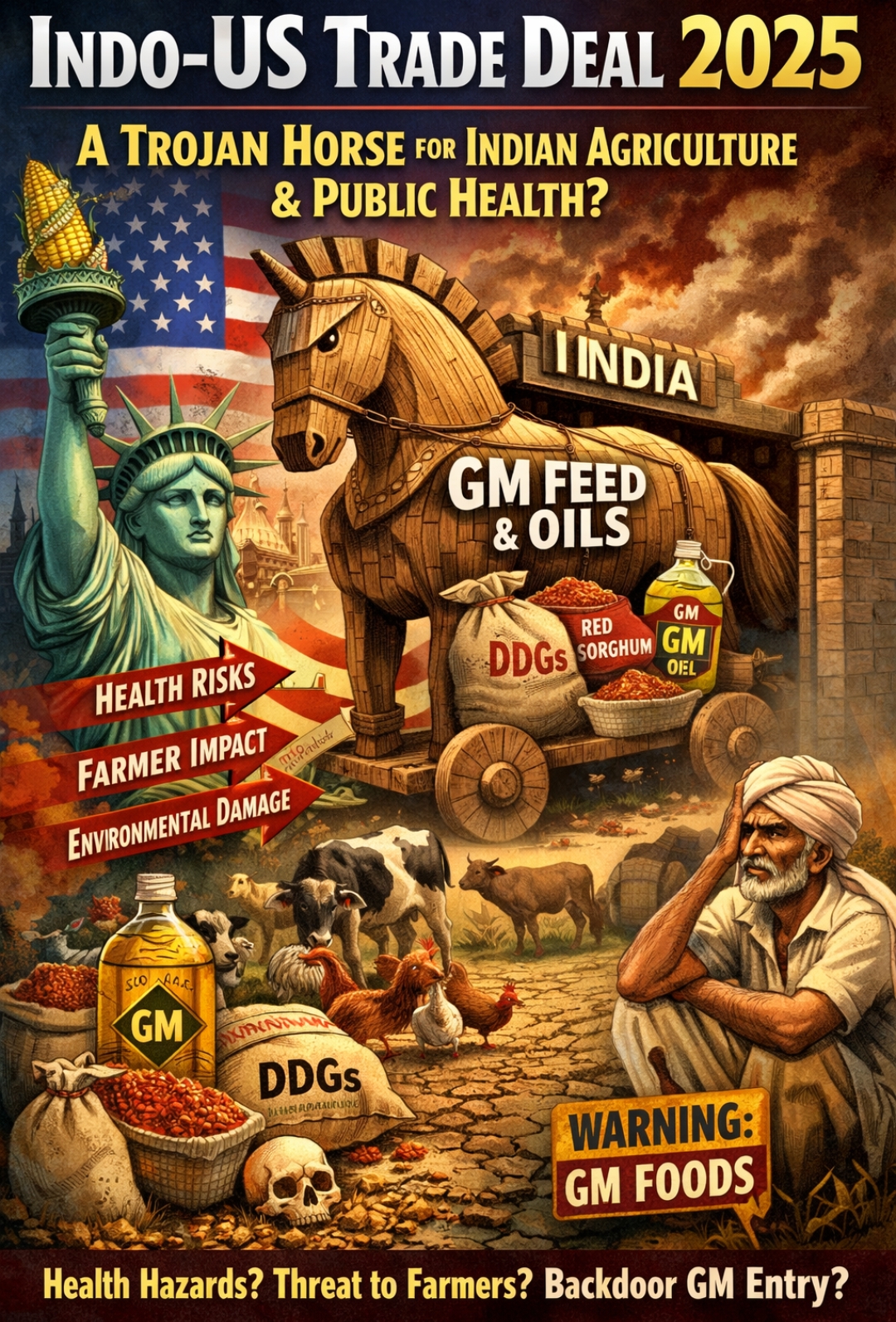

Indo–US Trade Deal 2025: A Trojan Horse for Indian Agriculture and Public Health?

The Indo–US Trade Deal of 2025 is being projected as a diplomatic and economic success, with the government asserting that India has successfully protected its red lines on dairy, corn, and soyabean imports. While it is true that direct imports of genetically modified (GM) corn and soyabean for human consumption remain restricted, the fine print of the agreement raises serious and unsettling concerns. India has reportedly agreed to reduce or eliminate tariffs on a wide range of American food and agricultural products, opening the door to imports such as animal feed ingredients like Dried Distillers Grains (DDGs), red sorghum, and soyabean oil—products that are overwhelmingly derived from genetically modified crops in the United States.

The most contentious element is the proposed import of DDGs, a by-product of ethanol production that largely comes from GM corn in the US. In India, DDGs are produced domestically from maize and rice, mostly non-GM, organically grown, and at a significantly lower cost. These indigenous DDGs are already widely used as feed for broiler chickens and cattle, supporting millions of small farmers and feed producers. Allowing large-scale imports of American DDGs not only threatens this domestic ecosystem but also raises a fundamental question: if Indian cattle, poultry, and livestock are fed GM-derived DDGs and red sorghum, will the resulting milk, meat, and eggs remain unaffected? The concern is not merely theoretical; it directly touches public health, environmental sustainability, and the livelihoods of Indian farmers who grow fodder and feed crops.

Equally troubling is the proposed import of soyabean oil, another product predominantly sourced from genetically modified soyabeans in the US. Soyabean oil is a mass-consumption edible oil in India, cutting across income groups. While proponents argue that refined oils no longer contain detectable DNA, scientific literature—including assessments by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)—clarifies that processing does not automatically negate the GM origin of a product. Genetic material or modified proteins may be reduced or denatured in highly refined products, but they are not universally or categorically eliminated. The claim that such imports pose “no health risk” therefore remains contested, especially in a country where long-term, independent studies on cumulative dietary exposure to GM-derived products are limited.

The joint statement’s vague assurance that India will “address long-standing non-tariff barriers to trade in US food and agricultural products” is perhaps the most alarming phrase in the entire agreement. To many observers, this reads like a coded commitment that could facilitate the gradual and indirect entry of GM food crops and products into India through regulatory dilution rather than transparent legislative change. India’s existing biosafety framework, rooted in the precautionary principle, has so far resisted such pressure. Any dilution under the guise of trade facilitation risks undermining years of regulatory safeguards.

The Commerce Minister’s assertion that genetically modified characteristics are “eliminated after processing” is, at best, a half-truth. Scientific consensus acknowledges that while certain processing methods can degrade DNA or proteins, this does not erase the GM origin of the product, nor does it conclusively rule out biological or ecological implications. Studies published in peer-reviewed journals and assessments by bodies such as the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) emphasize that each GM-derived product must be evaluated case by case, rather than being granted blanket clearance on the assumption that processing neutralizes all risks.

At its core, the Indo–US Trade Deal 2025 raises a fundamental question: are trade concessions being prioritized over food sovereignty, farmer livelihoods, environmental integrity, and public health? India’s resistance to GM food crops has never been rooted in anti-science rhetoric, but in the absence of long-term, India-specific impact studies and the need to protect millions of small farmers and consumers. Any agreement that potentially enables the backdoor entry of GM-derived products—whether as animal feed or edible oil—demands far greater transparency, parliamentary scrutiny, and public debate. Trade must serve the nation’s people, not quietly compromise their health, environment, and future.