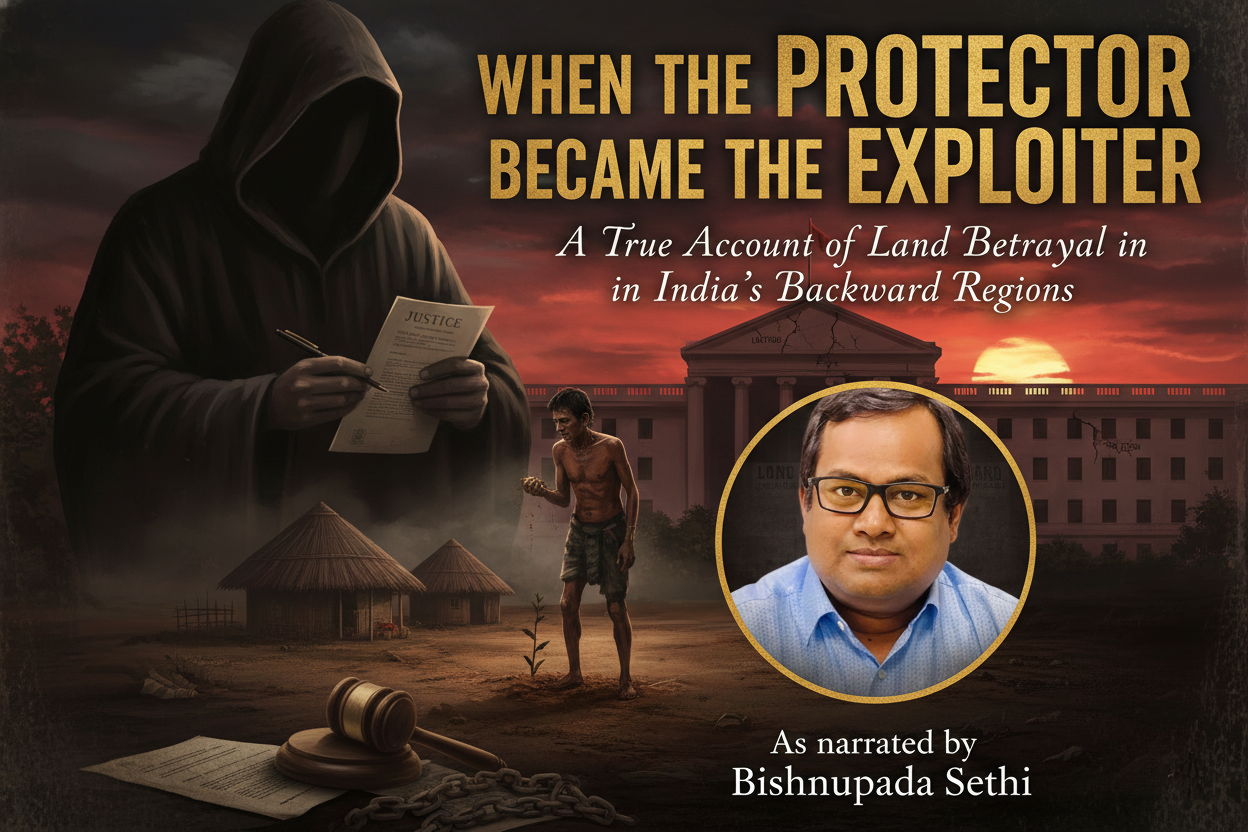

WHEN THE PROTECTOR BECAME THE EXPLOITER

(As narrated by Bishnupada Sethi to Giridhari Nayak)

Giridhari, let me tell you something that has stayed with me ever since my days in Rayagada.

When I took charge as Collector, Rayagada, it was a part of the larger KBK region, one of the most backward pockets of our country. Poverty there was not abstract. It was harsh and visible. In the tribal villages, people survived on small patches of land. For them, land was not an asset in the commercial sense. It was their only insurance against hunger.

Soon after I joined, Dr. Hrushikesh Panda cautioned me, “Be sensitive to tribal land matters. You will find that much of it has slipped away quietly.”

I took that advice seriously.

The Case That Opened My Eyes

One day, while reviewing files under the OSATIP Regulation, the law meant to protect tribal land from transfer to non-tribals, I came across a case from Gunupur. On the surface, it looked routine.

A tribal farmer, Raja Jagaranga, had sold two acres of land to another tribal man, Renju Sabar, in March 1993. Nothing unusual there.

But within a month and a half, Renju applied for permission to sell the same land to a non-tribal. The competent authority granted permission swiftly. The land was then sold to one Amulyanidhi Mohanty.

Later, it was transferred to Smt. Suhasini Das.

Now here is where it became troubling, Giridhari.

The Tahasildar who facilitated and processed the mutations was Sri Rama Chandra Das.

Amulyanidhi Mohanty was his brother-in-law.

Suhasini Das was his wife.

And Renju Sabar? He was working as a peon under the control of that very Tahasildar.

When I connected these facts, I could see the design behind what was made to look like routine paperwork.

How the Law Was Twisted.

The law clearly states that permission to sell tribal land must be given only in exceptional circumstances. The officer must verify genuine need, ensure no tribal buyer is available, explore alternatives, and confirm fair payment.

But in this case:

The applicant bought the land in March and sought to sell it by May.

Loan details were vague. No proper verification was done.

Mutation orders recorded that parties were “heard” when they had not even appeared.

Proper proclamation procedures were bypassed.

Welfare authorities were not informed.

It was all done in a hurry; but with precision.

When we later examined the widow of Renju Sabar, she told us she knew nothing about the land in Akhusing. Her husband had never discussed it. She had never seen him cultivate it.

That statement spoke louder than any document.

The Larger Tragedy

Giridhari, what hurt me most was not the technical violation.

It was the betrayal of trust.

In a backward tribal district, the Tahasildar is not just an officer — he is the State itself in the eyes of poor villagers. They cannot read regulations. They rely on faith.

And here, the very authority meant to protect tribal land had, in my considered view, engineered a benami transaction for personal benefit.

The land moved from a poor tribal farmer to a subordinate employee, then to a relative, and finally into the officer’s own family.

Meanwhile, the original tribal family was left nearly landless.

That is how exploitation happens in backward regions — not always through force, but through manipulation of process.

The Delay and the Defense

The matter had been reported by Vigilance years earlier, but inquiries dragged on. Reminders were issued repeatedly before a proper report came.

When we proceeded with review, the defense argued limitation — that five years had passed.

But how could limitation apply when the matter had been under inquiry all along? Justice cannot be defeated by deliberate delay.

The Decision

After examining the files, hearing the parties, and analyzing every irregularity, I concluded that the transactions were not free and fair. They were structured to defeat the protective law.

On 8 March 2002, in open court, I declared all the transactions void from the beginning.

I ordered cancellation of sale deeds.

I directed restoration of land to the legal heirs of Raja Jagaranga.

I instructed correction of the Record of Rights and delivery of physical possession.

What It Meant

You might think it was just two acres.

But in KBK, two acres can decide whether a family eats or migrates.

When the protector becomes the exploiter, the damage is deeper than financial loss. It erodes faith in governance itself.

That case reminded me that in districts like Rayagada, administration is not about grand announcements. It is about vigilance in small matters — because those “small matters” determine the survival of the poorest.

And Giridhari, that is why I always say: sensitivity to tribal land issues is not merely administrative duty — it is a moral responsibility.

Now you may be surprised that after I left the district, Sri Das moved higher offices and got favourable orders and the land in his name. Even his suspension and disciplinary proceedings were revoked. There was hardly anyone who saw the sinister design of the exploiters.